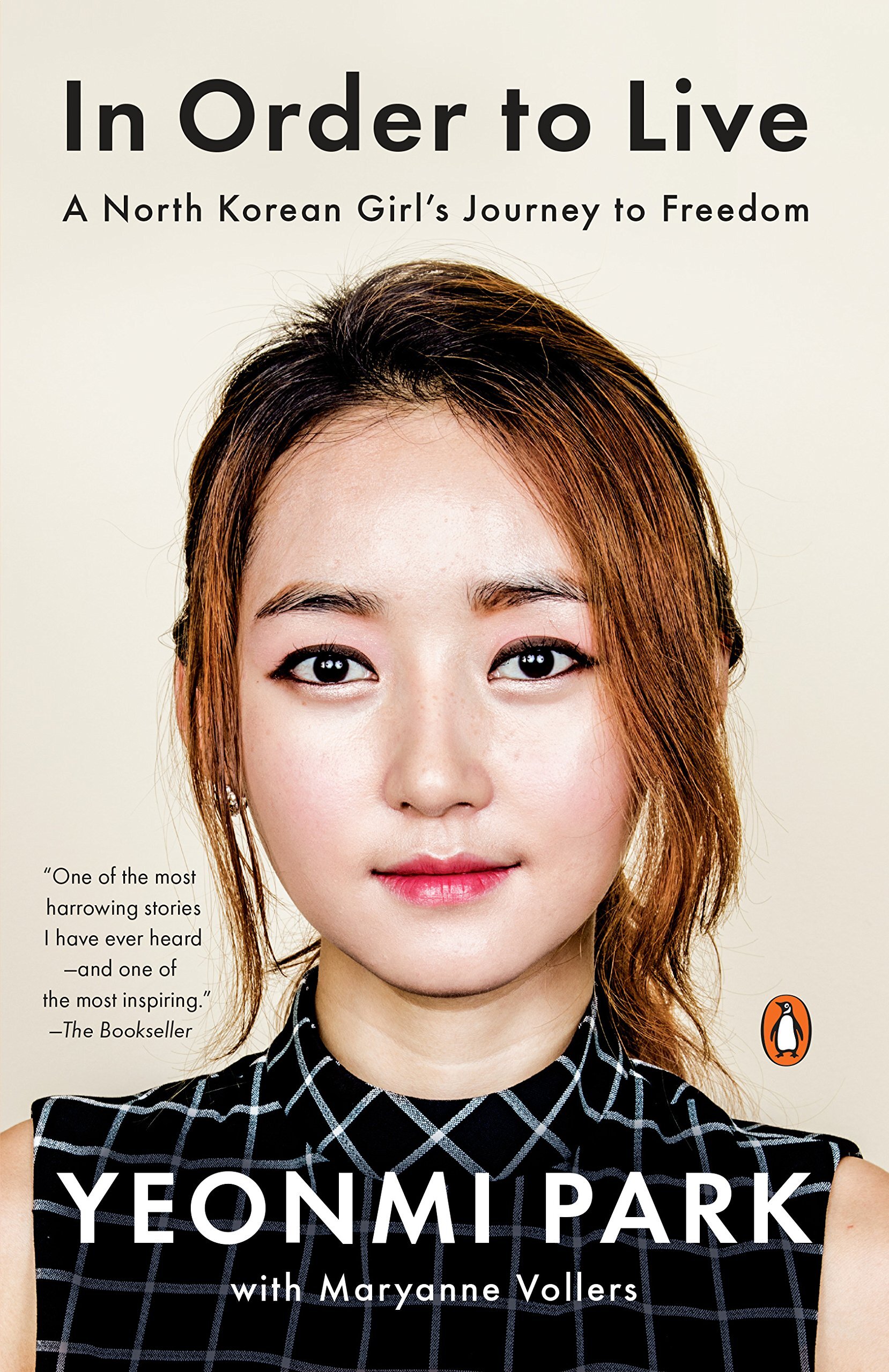

In Order to Live

In Order to Live: A North Korean Girl’s Journey to Freedom

By: Yeonmi Park (with Maryanne Vollers)

[Fulfilling “A book that takes place in another country” as part of the 2021 Spring/Summer Reading Challenge]

“The spark of human dignity is never completely distinguished, and given the oxygen of freedom and the power of love, it can grow again.”

In 2018 I read Ishikawa’s North Korean escape story called A River in Darkness and was shocked by how bad it really was in North Korea. Park’s story corroborates many things from Ishikawa’s experience, but hers is also different.

Both stories are heartbreaking and infuriating. Both stories showcase the power of resilience and the strength of resolve to survive and overcome.

But while Ishikawa’s story has a prominent thread of bitterness, Park’s story infuses forgiveness and a spirit of justice. She is on a path to help others like herself and to hold North Korea accountable for their atrocious governing and lack of care for their people (to put it kindly).

Yeonmi’s place in the North Korean social system as a young girl differed than Masaji, who was a farmer. So she didn’t have to experience some of the inhumane and utter desperation of complete starvation like Masaji, but at the same time, he never had to experience the abuse Yeonmi did as a woman being trafficked when she thought she was escaping.

It is obviously not a competition to see who was worse off, I mean only to recognize that there are many differing experiences of North Koreans who have escaped or who are still experiencing this oppression, but all stories’ common denominator is the evil that is ruling North Korea and the corruption in other countries as well, including China and Mongolia who do not stop trafficking and threaten (and carry out) the return of refugees to North Korea.

You can’t read a story like this without feeling admiration and awe that she survived what she did and went on to overcome the scars of her past and resist the North Korean stigma that ostracized her when she reached South Korea. The book is aptly titled— In Order to Live— because with each section of her journey— North Korea, China, South Korea— we are confronted with the impossible choices a person must make to survive.

So, because it’s a heartrending and inspiring story, I was curious what the 1-star ratings could possibly be about. Of course any book will have people who didn’t like the subject matter, found it boring, or just want to troll, but I was surprised to see all of the challenges to the veracity of Park’s story. There are links to articles exposing “inconsistencies” in her story, questioning her intentions and authenticity because she can’t keep her story straight. Others defend these inconsistencies, pointing to the ways trauma influences our memory and recall.

I’m not here to make a judgment, although it seems pretty crazy to call her a liar. I don’t know what is really gained by these accusations. The fact remains that regardless of the exact minutae of her story, North Korea is controlling and killing its people, humans are being trafficked all over the world, and people are being ostracized because of their country of origin.

The story forces you outside your comfortable US bubble to share in someone’s pain and encourage them in their triumph over their suffering. And it reiterates the need for all countries to hold each other accountable to protect human life.

To comment on an obvious political correlation, we peek into what life is like when the government controls the lives, history, religion, and discourses of their people.

Yeonmi says:

“I was taught never to express my opinion, never to question anything. I was taught to simply follow what the government told me to do or say or think… In North Korea, it’s not enough for the government to control where you go, what you learn, where you work, and what you say. They need to control you through your emotions, making you a slave to the state by destroying your individuality, and your ability to react to situations based on your own experience of the world.”

We can see inklings of this in America with the attempts to control language, silence dissenting viewpoints (especially in universities), demonizing certain people groups and blaming the world’s troubles on them, and discourage questioning of beliefs of certain people groups.

Regardless of politics, Park’s story also helped me to see America through the eyes of refugees from other countries. To see what they see and feel what they feel when they come into a completely new country with different language, customs, or even history, while still reeling with the trauma of their past and escape. We could do far more to accommodate and help refugees, to care for them, and believe in them to start anew.

And most importantly, as I stated in my review of Ishikawa’s book, these stories emphasize the need of the Good News, the hope of the Gospel, to reach these desolate places. The Gospel that defines the sanctity of life, a love unconditional and unending, the promise of justice and redemption, and the hope of something better than this broken world.

Pin this review to Pinterest!